A book for this moment in time ...

An insightful, deeply relevant history of a journalist and his deep awareness of the Greater Middle East ...

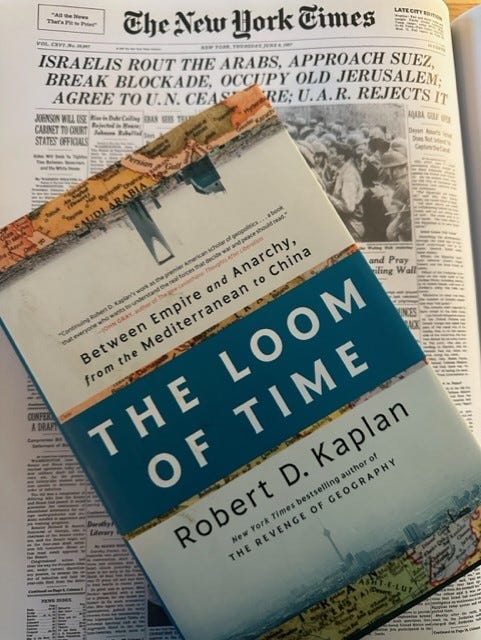

I was going to include the following review of Robert Kaplan’s book, THE LOOM OF TIME, with several others that are now on this site; however, I feared few would go from the letter to the site to read this relatively lengthy response to Kaplan’s book. While controversial and flawed, there is so much to be gleaned from this man’s 23rd book that I decided to give it a solo flight on a newsletter. I will follow this up shortly with another letter highlighting the other wonderful books one might read. Meanwhile, this is Robert Kaplan’s moment …

In my previous letter, prompted by the horror begun on October 7th, I recommended several books. One was THE LOOM OF TIME by Robert Kaplan. Having just finished it, scarring it for life with various forms of marginalia, I strongly recommend a hard look at this book. It is not for the convinced on either side of our foreign policy debates. Rather, the world he writes about, a world he has clearly LIVED in, is one resistant to armchair stereotypes. You might disagree in places but you will learn.

The book involves historical, cultural, and personal tours of Turkey, Greater Syria, Egypt, Greater Ethiopia, Iraq (& the Kurds), Iran and Afghanistan. Each chapter is rooted in Kaplans deep geographic, historical and on the ground journalistic knowledge of the country or region. Kaplan begins his personal tour of the Greater Middle East with Constantinople (a more historically evocative name than Istanbul). This chapter will eventually turn to Turkey both past and present. Before he gets there, however, using Greece as his backdrop, Kaplan goes on a historiographical digression that can be lightly skimmed until he gets to Edward Gibbon and his magisterial seven volume history, THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. I think I know one person who has read all seven volumes. I have barely made a dent in a huge, abridged version. His sentences, like Hemingway’s a hundred years later, changed our idea of syntax – the Gibbonian sentence and its endless commas, subordinated clauses, and musical rhythm. If Hemingway was trying to reduce language to accommodate the subjectivity of modern individualism, Gibbon was opening language up to underscore the labyrinthian realities of history in general and empire in particular.

Like Kaplan, Gibbon was obsessed with Constantinople, the history of the Eastern Roman Empire and its Eastern Orthodox Byzantine reincarnation after the fall of Justinian in the 6th century. We always attach “Rome” to the grand expanse of the Mediterranean centered Roman empire but forget that its eastern version launched by Constantinople lasted almost 1200 years and was a bulwark against the tides of aggression that consistently swept through the Near East, protecting a dark and illiterate Europe long enough for it to edge toward a post Roman rebirth. Gibbon’s obsession occupied his last set of books and Kaplan argues that our “pc” fired prejudice against a profoundly literate 19th century British historian combined with his controversial emphasis of Christianity’s role in Rome’s fall have obscured the best of his work. In the last volumes, Gibbon argues (according to Arnold Toynbee) that empire ‘protects politically immature people from themselves and their neighbors.’ That the geopolitical tyranny and anarchy which we are experiencing so viscerally today comes from the fear that arises when order is dismantled. This argument can scare people – understandably. It too often is a gateway rational for authoritarianism. It lies inside much of what we hear from the alt right (e.g., “start shooting shoplifters”). Regardless, Kaplan’s march through the history and the geography of the Greater Middle East suggests that “order” has always been and always will be the order of the day for so many entirely rational reasons. Order can mean many things, in the very BIG picture of Kaplan, it means “empire”, both real and imagined.

Kaplan will utilize dozens of other historians, journalists, and thinkers in the same way in this book; however, Gibbon joins Arnold Toynbee and Samuel Huntington as the guardians of his central thesis – the critical role of empire. There is so much to be discussed in this learned, ambitious book with its controversial central thesis by a man who has lived in the countries he writes about and can count this book his 23rd effort to understand our world. Look closely at the list of his published books and one sees the rare combination of pure scholar, intrepid traveler, and fearless journalist. The book has a summation feel to it and its timeliness is stunning. Critics have flinched at the book’s unapologetic realpolitik theme. I suspect some are ‘too young to know’ that the realpolitik of Kissinger, Arendt and other 20th century scholars and diplomats arose from being deeply acquainted with history’s long dance with evil … a dance whose tune can be heard more clearly than ever these past couple years. If you think the Arab Spring was a good thing, that Obama did right by Libya and we should have intervened in Syria, then this might not be your book. If you wish we had left Iraq alone in 2003, organized a much more thoughtful exit from Afghanistan and believe that democracy may not be in the Greater Middle East’s distant future, then dive in.

I strongly urge any reader interested in history’s ability to inform the present to find a bookstore nook and read his Introduction: “Time and Terrain”. Students from my history classes will recognize shades of my foreign policy arguments in this Introduction. Thus, this book feels personal in many respects. No small bit of writer’s envy combined with a sense of validation instills in me a sense of urgency when it comes to recommending THE LOOM OF TIME. Kaplan’s opinions are based on extraordinary levels of experience and scholarship all the while leavened with honesty. He knows when he misread things and fesses-up, no more poignantly than over his misguided support of the Iraq War where he strayed from his own deeply held set of historically based convictions. I suspect he continues to pay a price for this.

This is my personal newsletter plug for the book. It is not at all a perfect book. When he lets go of the historical backbone of his work and drifts into current event prognostication, his clarity and insight fade into the treacherous crystal ball waters trafficked by pundits. Even the recent horrific events in Israel leave him on a lonely limb in more than a couple places. There are too many interviews that allow a certain redundancy to creep in. However … getting back to Gibbons and Toynbee among others, great minds stray.

Thank you

…