Newsletter: a "catch-up"

Summer and early fall readings that may ease our way to 11/5

After the “history lesson” newsletter on Chernow’s Grant, I thought I might send out a clean-up letter citing recently read books I have neglected to put on the site. This is a long letter so I will list the books that I comment on enabling you to skip as much as you want. Warning: there is yet another Cormac McCarthy plug at the end.

The following books are discussed in brief in this newsletter:

Martyr! … a novel by Kaveh Albar … (2024) 352 pages

Absolution … a novel by Alice McDermott … (2023 ) 336 pages

Caledonian Road … a novel by Andrew O’Hagan … (2024) 624 pages

You Are Here … by David Nichols … (2024) 340 pages

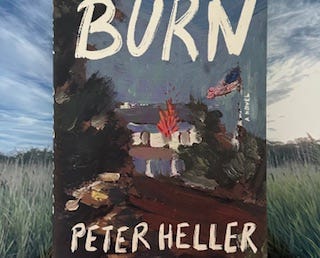

Burn … by Peter Heller … (2024) 304 pages

Precipice … by Robert Harris … (2024) 464 pages

Clear … by Carys Davis … (2024) 208 pages

Old Filth … by Jane Gardham … (2006) 289 pages

The Marriage Portrait … by Maggie O’Farrell … (2022) 352 pages

Fire Weather … by John Valiant … (2023) 432 pages with notes

The Drop … by Dennis Lehane … (2014) 224 pages

The Friends of Eddie Coyle … by George Higgins … (2010) 192 pages

Martyr! is an edgy book. The title’s exclamation point and the cover drawing suggest a lot. I read it, listened to it and, at the end, read it. While the audiobook reader is out of this world, the writing is beautiful and must be read to be fully appreciated. Another autobiographically structured novel, Martyr! soars above its memoir roots. It is in equal parts excruciatingly honest, moving, unnerving, and funny. Rooted in a Ven diagram of youth, gender, immigration, and drugs, the story’s narrative and its many themes are tied together by an artful combination of art, fable, and poetry. The chapters in the Brooklyn Museum of Art soar. While its energy can lead the reader into narrative cul-de-sacs, its Iranian narrator’s voice will stick with you forever. I confess that its youthful “otherness” made me anxious and censorious at the outset but thanks to the audiobook intervention I reconnected and am so grateful to have finished it.

NOTE: the writer made a brief visit at the Sun Valley Writer’s Conference (SVWC). He stole the show in a Q&A that he had to share, unfortunately, with another less talented writer. His on-stage presence was the Martyr!’s narrator incarnate.

Absolution deserves a much longer response. Alice McDermott is on my short list of great contemporary writers. I have read most of her books and disliked only one (Charming Billy). The books are serious, modest, and filled with grace and insight. Kristin Hannah spoke about her nurses in her Vietnam bestseller at the SVWC. She and the book were and are great hits. Her book, The Women, is an important untold story that packs a punch. Absolution is another Vietnam novel structured around women but if Hannah’s book is a great story, McDermott’s is a great novel. A great novel is not formulaic. E.L. Doctorow once compared writing to driving at night … you only see as far as the headlights in front of you. The same applies to the reader’s experience with a great novel. The opacity that engulfs you is created by all its resonant elements: its evocative writing, the arc of its characters and its ability to rise above the plot. McDermott writes about women’s interior and exterior lives, whether they be nuns, housewives or, in this case, Army spouses. In Absolution, the young, innocent protagonist “grows up” in the emerging chaos of Vietnam, not in the bloody tragedy of the hospitals but within the paper-thin walls of Saigon’s American “cocktail society”. The drinks and dresses soon mingle with lepers and bombs as the novel traffics, in a subtle and unpretentious manner, the role of love, loyalty and faith in the midst of an alien and dangerous world. Like Hannah’s blockbuster, Absolution continues on, briefly, to life after Vietnam. By the end, one is left pondering about the wonderfully suggestive title. Who is “released” from what? It is McDermott’s nod to her spiritual roots and the final exclamation of a great novel.

Caledonian Road is a long novel that warrants every page of its length. Eminently readable, witty, and relevant, O’Hagan’s book reads like a more restrained, Scottish version of a Tom Wolfe satire. He certainly does to London circa 2020 what Wolfe did to Eighties New York. The narrative sketches a canvas as vast as the city itself. There is a Dickensian list of characters after the title page that comes in quite handy. The chapters are, however, coherently organized and it quickly turns into a very literate page-turner. Much happens. Money laundering is at its center along with a cast of nasty Russians; however, the “laundering” extends well beyond its monetary space into marriages, gangs, the art world and much of what shapes our thoughts about London and our money drenched world. The protagonist is an insightful, talented white 52-year-old man with a good life, sketchy friends, and an open mind who begins to slide into an existential crisis that mirrors the themes of this ambitious novel. Employing generation gaps and the Internet among other things, O’Hagan pulls off this narrative juggling act. I do wish he had exchanged a couple plot lines for further exposition of his charismatic protagonist. Regardless, this is a minor criticism in an otherwise deeply engaging novel.

I loved the television series “One Day” for several reasons. While too long and a bit corny, the show was moving, funny, and literate. It was based on a novel by David Nichols. I soon did a bit of a dive on the talented Nichols and was thrilled to discover that his latest, You Are Here, was met by waves of enthusiastic reviews. Like “One Day”, it is a bit too long and tips into the formulaic but rights itself quite brilliantly by the end. It is a very funny novel laced with insight and penny philosophy. Critics (at least the NYT) are increasingly obsessed with the “debut” novel. A “debut” may be crowned a “must read” because of its shock value, the poignancy of its relevance or as yet another groundbreaking sexual adventure. What is too often not there is the wry wit and comforting perspective that comes with age and years of writing. David Nichols is just the antidote to the tyranny of the “new”. An additional thanks is that I have always wondered about walking the neck of northern England and now I don’t have to.

The cover tells it all. A spooky, tight novel about a post-democracy America. Set in the woods and waters of Maine, it is typical Heller. This is my third Heller. He gets better each time. His stories are very male. Cormac McCarthy without the metaphysical, Hemingway without the art … more like Dashiell Hammett in jeans driving a pick-up with a gun rack. What elevates this book in particular and, to some degree, all his other works is a contemporary context that gives a true chill to his taut prose. In this case, it is a gradual and scary reveal of the anarchic consequences of another January 6th moment that triggers a spasm of violence in the woods of Maine and, we suspect but don’t know, elsewhere. We know very little throughout this page turner. I wish Heller had written less backstory and kept his narrative within the terror of the story’s slow, opaque reveal. Regardless, the beauty of Maine infected with blood and fear makes for disturbing backdrop to our upcoming November plunge.

I consider Robert Harris’ Cicero trilogy one of the great reads of my life. The first book, Imperium, is a “must” read for any one of the following: historical fiction fan, Roman Empire historian or political junkie. Ever since, I have remained a devotee of one of our finest historical fiction writers. Harris occupied this genre way before it became au currant. His books are uneven. The most recent, An Act of Oblivion, will likely remain there forever. He wrote it during the pandemic and supposedly is embarrassed by it. In Precipice, he has returned to his fine form … in fact, he may have reinvented himself a bit. The story begins in the fateful month of August in the fateful year of 1914. It is based on an extraordinarily inappropriate affair between the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and an engaging woman from the English aristocracy who is 40 years his junior. Much happens in the back of the “Prime’s” Daimler including the exchange and littering of state secrets. It flirts with being a bit redundant but its supporting cast ranging from Winston Churchill to Lord Beaverbrook combines with the harrowing events of the war to keep you flipping through to the end. The pleasant surprise, however, is how effectively it frames the eternal dilemma of the personal mixing and coloring the political. The Greeks might have got this ball rolling with the Iliad and “Antigone”, but Harris provides a startlingly reprise within the context of the great modern tragedy of WWI. The letters delivered daily between the two lovers are the real thing. Their very existence is as remarkable as the fact that the Royal Mail delivered letters up to 12x a day at the turn of the century. Maybe social media was not that big a jump … anyway, this is a really fun and, ultimately, provocative return to form by Robert Harris.

I read a great review in The Spectator of a strange but beautifully written novel, Clear. The review convinced me and I read this short gem over a few days. There is nothing “clear” about this odd tale set in the remotest of Scotland’s northern islands … except her writing. She writes like a saint. In fact, her setting, its plot and particularly its characters are not at all mirrors of their 19th century world. One is transported into a spiritual world of paganism and mystical Christianity with no hocus pocus or literary tricks. Davies’s jacket photo suggests a fiercely independent woman comfortable in the figurative and metaphorical wilds of her northern Scotland. Not that she is provincial. I was given her first novel, West, by a friend a couple years ago. It is short and takes place in Kentucky. I got sidetracked and must now return to it. She is a disciplined writer who writes NOVELS … not historical fiction or memoirs in disguise. It is refreshing and increasingly rare to read a novel launched from the writer’s imagination as opposed to the cheat sheets of history and autobiography. Not that either of those genres are second class, they are simply overcrowded and as the volume increases, the quality degrades. I get it. Historical fiction is a place where the competent likes of Kristine Hannah can contribute to a more inclusive and honest historical record and the endless memoirs are very often the voices one never heard in the not too recent past. Regardless, a writing voice like Davies is a reminder of the joy of the pure novel.

(PLUG: please read The High House by Jessie Greengrass. Another example of a pure novel, one of the best I have read in the last ten years.)

As the gap between ME and CONTEMPORARY FICTION continues to widen with age, I am now beginning to return to favorites that have receded into the cerebral mist just enough to allow for a fresh reading experience. I swallowed Gardham whole many years ago - the trilogy and a couple of her shorter works. Old Filth was the first novel I read and still is considered her best. It more than held up on a reread. The structure made more sense and its central themes of lost childhood and lost empire seemed much more elegantly paired than during my first reading. I have encouraged many to read this bittersweet, often funny, impeccably written ode to a lost world that keeps nostalgia at an ironic arms’ distance illuminating all too freshly its multilayered poignancy. This is the kind of novel that is fading amidst the soup of memoirs, subjective polemics and poor historical fiction that is our noisy but too often insubstantial fare. If this sounds a bit snarky, please read it and, if I am wrong, feel free to hang me out on the boomer wash line.

Too often the novel that comes after a critical and popular success is a keen disappointment. Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet was a joy to read – in every sense. It was more an act of imagination than a work of historical fiction. It captured the souls of its principal characters while avoiding the temptations of a feminist polemic. Finally, it was beautifully written with and a gift of an ending. Thus, The Marriage Portrait stared at me from its shelves as yet another disappointment in the making … Charlie Brown and the football. It took two years and several good reviews from fellow literary travelers to persuade me to tackle a book that tells you from the start that its beguiling heroine will die a brutal and young death. Not unlike so many of her Irish peers, death haunts O’Farrell’s work. Her shockingly original autobiographical I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death puts paid on this clear obsession. As she has done in her other works, she employs the surety of her heroine’s death to expand the reach of the true story from the more black and white terrain of historical fiction to the nuance of the metaphorical. The book is too long with descriptions that are a bit too drawn out. The ending, however, is carefully drawn and sublime and worth the wait. She is a gifted writer who raises the feminist novel to the highest of literary levels

.Fire Weather is an overheated, searing account of the terrifying Fort McMurray fire in Alberta, Canada that burned much of the oil boomtown down and stands as a warning of the fires to come as the planet heats up. Valiant grabs you by the throat from the start. His descriptions of the fire are extraordinary. I will never think of a great fire the same after reading this. His contextual treatments are too many and too long; however, much will stick. The descriptions of the men and equipment involved in the massive oil sands landscape left me dumbfounded. It was as if I was reading about another planet. I never understood the long history of man and bitumen (tar). I did not know how early the climate warnings began (circa 1860). There is so much to take it. Reading this book is like sipping from a fire hydrant and that is its weakness. Once again, my siren call for an EDITOR! This book needed serious trimming. Seeing him at the SVWC it was pretty clear that an editor might have a hard time reining him in. Regardless, its repetitiveness and its endless amount of detail leaves one tired and undermines an engaging cinematic writing style and a story that stands out among the many terrifying climate narratives that now inhabit our conscious and unconscious lives.

This summer, Jeannie and I started our drive back from Sun Valley listening to Dennis Lehane being interviewed at the SVWC. It was riveting. In it he plugged his most recent novel, Small Mercies, as his best since Mystic River and The Drop. I wrote about Small Mercies in an earlier letter. I was utterly absorbed and thrilled by this short piece of literary dynamite. Listening to its audiobook version only made Lehane’s book even more astonishing. I was determined to read Mystic River after listening to another version of the unforgettable Mary Pat. I also ordered The Drop. The latter was waiting for me when I got home. It is very short and sweet. It was written to be a movie but that is one of Lehane’s many gifts. His stories have the narrative energy of film with dialogue that may rank as the grittiest and funniest I have ever read. The Drop was drop dead good and now it was Mystic River’s turn. A couple weeks later. I walked into a local bookstore in New York looking for Mystic River. It was not in stock with Small Mercies being the only Lehane in stock. This small but excellent shop is staffed with great readers so I asked “Nick” if he had read Lehane’s latest. I urged him to read it and he then reached into the shelves and pulled out George Higgin’s 1971 classic, The Friends of Eddie Coyle. He was surprised that I had not read it. We agreed to read the books we had just recommended to each other. That was a very satisfying reader’s moment for several reasons but one is that I was blown away by the short genre founding book of Higgins. I guess this book led to the whole Boston noir thing with Lehane being a full member. In fact, Lehane writes the introduction to the latest edition of The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The book is 90% dialogue. I read it in two days. The movie is a classic and also spawned the long list of Boston crime flics. All of these books (and their movies) crawl out of the same Boston swamp. Pick anyone of them and read it. They are so good.

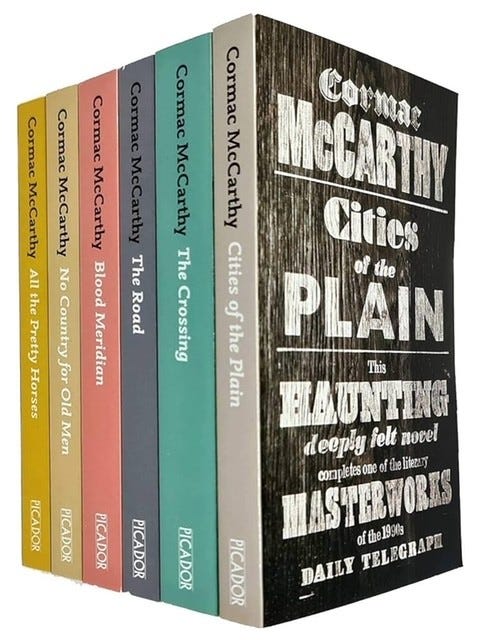

The drumbeat continues … another shout-out for Cormac McCarthy.

The rereading of Cormac has begun. The third book in his Border Trilogy, Cities of the Plain, is the cleanest example of the pure McCarthy style. At its best it reflects a scriptural version of Hemingway that perfectly matches both subject and theme. The Road achieved this in ways still under appreciated and cheapened by the movie. Also, given how are existential selves have morphed in recent years, it feels almost unbearably prescient; however, its style is the perfect marriage of language and content. Right behind The Road is Cities of the Plain. It will break your heart but in a simpler and more direct way than the first two books of the trilogy.

Rather than beat this drum any further, I will rank his books with a brief commentary. While they all share a millenary vision of humanity, a genius for place and time, and an extraordinary ear for dialogue, it is their differences that truly magnify the genius of McCarthy.

The Road … a classic when published and for good but very painful reasons. Note the “fire” metaphor … a staple of his.

The Passenger … not for everyone. Should be read with Stella Maris and after two screenings of “Oppenheimer”. Some of the best dialogue I have ever read.

Stella Maris … breathtakingly original … difficult – must be read with The Passenger … a brother / sister act in every sense.

Cities of the Plain … as noted …

All the Pretty Horses … in some ways a bit too elegant but in a class of its own when published.

No Country for Old Men … the movie is better … may be one of the greatest American films but could not have been done without this in one sitting screed about our violent world.

The Crossing … I need to reread this as I struggled with it years ago and it may have been a case of bad timing.

Blood Meridian … on so many lists … I do not agree. I forced myself to finish it. It embraced an earlier more purplish, flamboyant style (see Sutree) that he, thankfully, walked away from.

Thank you … good luck with November.