Newsletter: The Seven Books - Part Two

Three very different non-fiction titles that shaped and affirmed ...

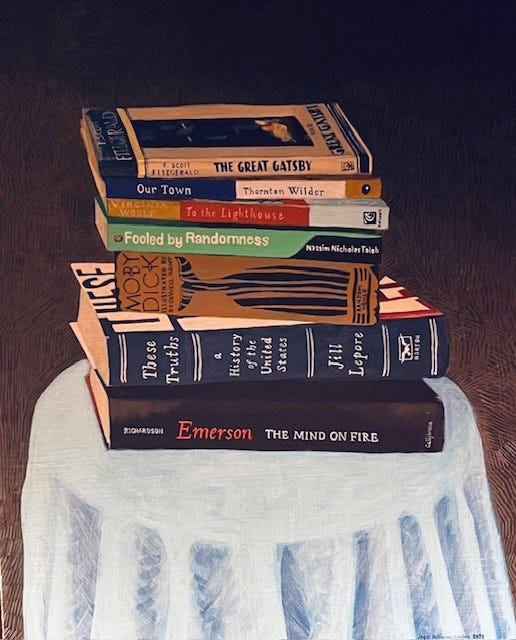

Last February I wrote about the SEVEN books project initiated by my wonderful wife, Jeannie. It involved selecting the seven books that most profoundly shaped my life and thoughts. The books were chosen and the resultant beautiful painting is on my website. It stands as the greatest gift in my life. My winter letter addressed an Honorable Mention list that arose in the process. This letter, however, will address the non-fiction half of the seven books memorialized in the painting.

Understanding money in all its layered significance was and remains one of the great challenges of my life. I left the world of finance and embraced a genuine vocation teaching the deeply loved subjects of American Literature and American History. Any idea that I had walked away from money, however, was pure fantasy both in terms of my personal life and, most ironically, in the arrival of a novel Investment Class alternative for seniors that was built around my place in the faculty and my background. It was, in hindsight, an act of grace. Teaching seniors the mechanics of investing quickly blended into an on-going discussion about the role of money in our lives. I returned to the markets, read many important books and through the role of teacher gradually found my way to a greater understanding of a subject that affected my thinking as much as any other force in my life. The book that I most often quote, that I repeatedly assigned for summer reading and remains a totem in my thinking not just about money but life is Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Taleb. Taleb would later launch himself into international celebrity status with the “black swan” phenomena but this book is the early glimpse into the foundation of this brilliant man’s ideas about money and human nature. Reviewing it, I realize how much of what he wrote has been incorporated into our current psychological understanding of money. Many who have read it, including students, got a bit bogged down in some financial quantitative work that is spread throughout the book and concentrates a bit near the end; however, this can be skimmed, even skipped. Like panning for gold, his nuggets of insight that shimmer throughout the text, always both personal and anecdotal, are “take home” lessons for life.

I had taught American Literature for barely under two years when one summer I thought I would revisit the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In the end, I chose “Self-Reliance” in its entirety and excerpts from a few others as the basis for a module on a period of literature and philosophy that has often been called the American Renaissance. The mid 19th century movement was framed by Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller among many others. At its core it was an argument around the idea of Transcendentalism. It was the perfect framework for the marriage of literature and philosophy around a central question: is man part and parcel of an inherently good and accessible universe or is he alone in an indifferent, random, and Godless world? With Emerson on one side, Melville on the other and Hawthorne tacking in between, it became the basis for a winter quarter of philosophical, literary, and personal debate. It was likely my most original and risky effort as a 10th grade lit teacher and it acquired personal meaning for me when a few years after embarking on this difficult pedagogical effort, I read Robert Richardson’s Emerson: The Mind on Fire. This pure literary biography tracks the growth of Emerson’s mind as the Concord philosopher covers most of the intellectual, theological, and artistic landmarks of human history. Whether it is in the teachings of the East or the emerging Romanticism of Europe, each foray is coordinated by Richardson into a mosaic of thought that illuminates a brilliant mind at work. Emerson is not easy to love even if he is our most quoted philosopher. His arguments often feel contradictory – sometimes in the same sentence. His idealism can grate on a modern sensibility. His prose gets tangled amidst its density. Under Richardson’s insightful stewardship, all this sub-atomic chaos feels thrillingly alive and truthful. His book not only helped justify and ground my winter quarter, Emerson: The Mind on Fire gave me permission to continue my own restless searches.

The final non-fiction selection is not only one of the books that shaped my thinking, but also is one of the great books of my life – period. Jill Lepore’s These Truths is a retelling of American History through the lens of our original sin. This has been done before but too often with rancor and a bias as denigrating to the author as those he or she might be targeting. Lepore is a national treasure. A wildly popular classroom professor at Harvard, a regular contributor to The New Yorker, she is among the most versatile and eloquent spokespersons for not only American History but for the whole concept and conceit of history. I read her after teaching. It broke my heart. She would have inspired me to redo my entire approach. I gave her book to many people and those who read it were deeply moved and changed by the experience. Race is at the heart of this country. Maybe private property comes as close but even that has had to be filtered through our original sin. It is the ghost haunting our current election 305 years after the first slave ship, 237 years after the birth of our Constitution, 159 years after the Civil War and 55 years after the assassination of MLK. All those years are treated with an outraged, contained dignity by Lepore as she rewrites and simultaneously redresses our violent history. With scholastic empathy, the iconographic landscape of our history remains intact, just relocated to a shadier more nuanced environment. To accomplish this deft act, she stays away from too much political detail, from military history and from the more jingoistic fluff that filled the textbooks I had to work with over the years. The famous line from “The History Boys “that history is “just one fucking thing after another” does not apply to These Truths, the most elegant and relevant synthesis of American History I have ever read.

My usual critics newsletter will come in a few weeks. It will be a real hodgepodge of old and new, print, and Audible. This coat of many colors is a product of personal distractions, macro anxiety about the world at large and a fear that the publishing world is moving even further away from me. The fiction world has truly changed. I have discussed this before but I feel it bears further reflection. It is NOT an accident that the stepchild of the novel, historical fiction, is increasingly front and center. While it may be a part of rewriting our collective histories, I also fear it comes from a crisis of imagination triggered by an existential fear of the future. The purely imaginative act of fiction is intimidating and requires a freedom to safely imagine. Our catastrophically and too often hysterically drawn world removes the cocoon required to allow the imagination to run free. Whatever the reasons, the fictionalization of history mirrors similar blurring of literary borders whether they be the ubiquitous “fictionalized” memoir or the “fictionalizing” of social issues and inequities traditionally reserved for the different formats of the non-fiction world. Maybe the philosophers and pundits have been right all along. The personal is now indistinguishable from the political. Of course, this bout of fiction ennui may simply be an aging boomer facing not only an unsettling world but a mortality that inherently overweighs the past at the expense of both the present and the future. Maybe …

Thank you for reading

…