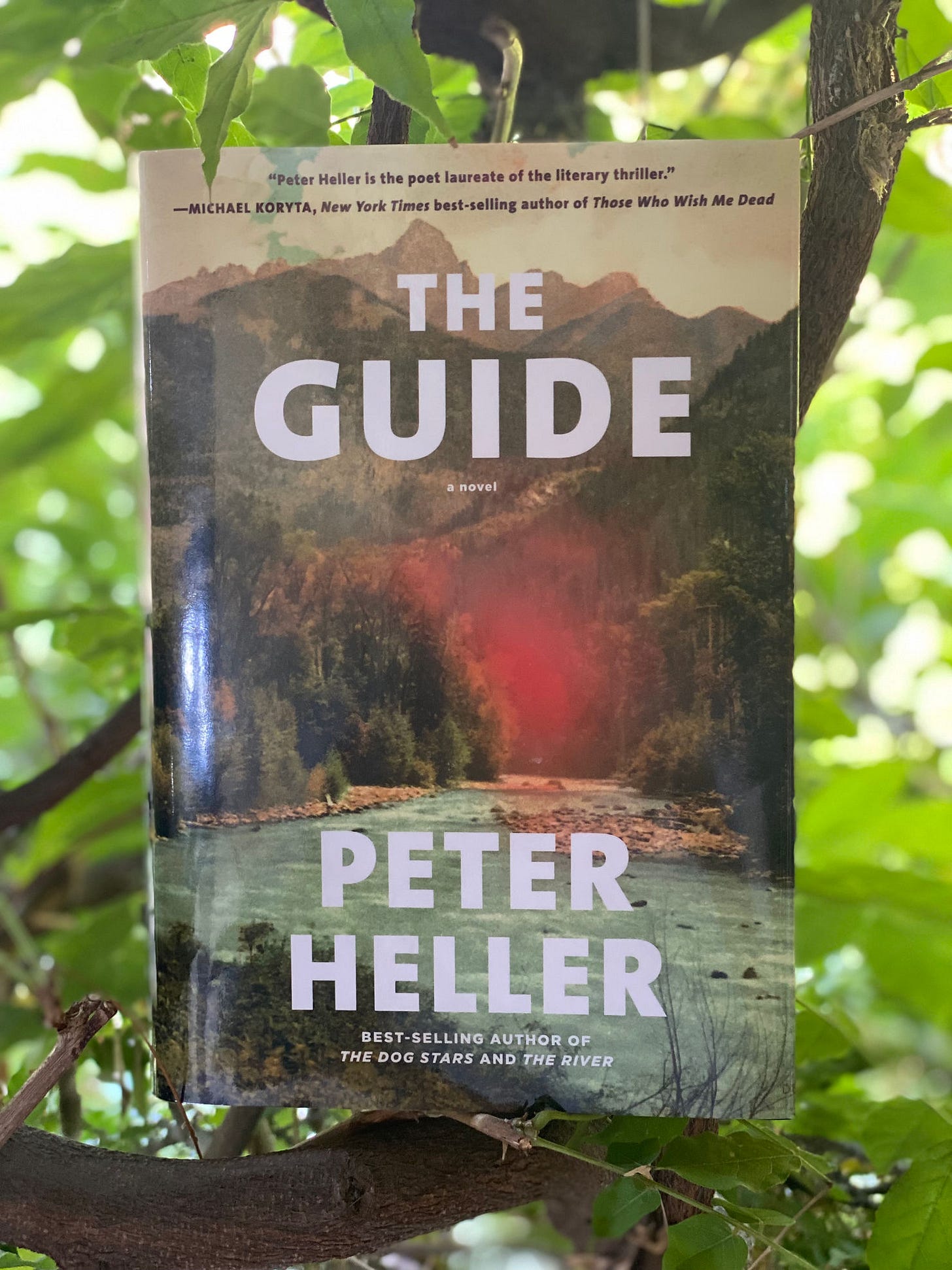

Review of THE GUIDE

What is a "literary thriller"? Heller's good book is a good "guide".

There are books that fit perfectly into a certain liminal moment … the airplane read comes first to mind. If the “not too long”, engaging book is well-written with strong fully developed characters, the critics often label this “airplane read” as a “literary thriller”. The distinction between a “mystery” and a “thriller” is a bit like the difference between an introvert and an extrovert. Mystery writers like Louise Penny and PD James create detectives and narratives that can admit many philosophical digressions as the reader follows the internal ruminations of your favorite detective. The thriller of David Brown or James Clancy, on the other hand, is a series of events that unfold before your eyes. Think James Bond. Thus, “literary” mysteries are more common because they are more inward focused while thrillers are rarely considered “literary” because they are driven by the external imperatives of a riveting, fast moving plot. Peter Heller’s The Guide is consistently labeled as a “literary thriller”, a category that I consider close to qualifying as an oxymoron. I read The Guide hoping that it was, in fact, a groundbreaking “literary thriller”. It is not. It is, however, a terrific, very well written read.

After reading (in three days) The Guide, I will not go so far as to say that calling a book a “literary thriller” is an oxymoron but if I heard someone else make such a statement, I might not object. A “thriller” implies a book powered by its plot – often a plot filled with the unexpected … and, honestly, the implausible. It makes for very entertaining films but if one is truly honest and can separate from the adrenaline rush, almost all the “thriller” films end flirting with the absurd. Jason Bourne should have been dead a long time ago. It is a pact we make with the cinematic version of the genre, and it is no different with its written word counterparts. The danger is calling it literary. Name a movie thriller that over the years evolved into a classic that is not science fiction? It is a short list that might start with The Third Man and much of Alfred Hitchcock (see below). A “literary” thriller is equally rare. I propose that when one uses “literary” in this context one is suggesting the possibility of qualifying for some sort of classic standard. Thrillers in both artistic forms are too often Alka-Seltzer tablets no matter how artfully done. Look at Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. In its novel form, it is a thriller. In its cinematic form, it is a classic. The novel reads in one sitting. It is riveting but without the film it might have been forgotten by now. The Cohen brothers took it out of its thriller context, opened the lens and created a sweeping American masterpiece whose rumination on evil, America and change made the book’s suspenseful plot a co-pilot to its more profound cinematic incarnation. Trapped within its one sitting thriller genre, the book never comes close to the film.

Thus, my quibble with The Guide. The demand of the plot takes it into a far-fetched space that undermines the solidity of his writing and the deliberateness of his characterization. While it forces you to finish it, there is little for you to think about in the end despite its virus twist. BUT … it is worth reading. The thriller is to fiction what the slide used to be to pools. Fun.

NOTE: the great exceptions to my equally great generality about thrillers, are Hitchcock in film and Le Carre in literature. Not all of Hitchcock’s films qualify just as many of Le Carre’s books don’t. In each case, the likelihood of a cinematic or literary thriller from either declined as they got older. However, Le Carre’s Smiley novels are, in fact, pure literary thrillers. You want to know what happens next. There are twists and turns. But within this maze of shifting layers of suspense is an atmospheric representation of the Cold War I have not read anywhere else. This evocative representation lifts his characters and their actions into rarified space. It is no accident that once he left the Cold War, the alchemy was gone. Third World violence, the Middle East, the War on Terror … they serve simply as sets for predictable plots sustained by his writing gift. The profoundly intimate context he brought to the Cold War is not there. These contemporary efforts leave you with no literary impression. A real piece of literature becomes a part of your memory, it helps shapes how you remember your life. It is a lighthouse within that foggy world we call the past.

Like Le Carre and the Cold War, Hitchcock also loses a lot of traction once he leaves the Fifties and early Sixties. There is always something not right in his world despite beautiful blondes, Cary Grant and great taste. Wasn’t he foreshadowing the darkness that we are now coming to terms with so painfully when digesting post WWII America and the “American Century”? His “thrillers” suggests that there is trouble in paradise without a finger pointing at you, the viewer. They all came for the thriller but left with an impression that might linger for the rest of their lives.

The Guide

Peter Heller (2021)

257 pages