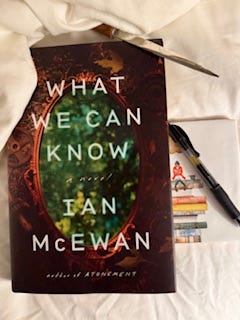

Review of What We Can Know

Ian McEwan steps up and writes a big imperfect novel that matters ...

I am hard pressed to find a writer whose oeuvre I have read more of than Ian McEwan. It began with the harrowing Child in Time that many consider his finest (though clearly almost unreadable for any parent). I recall a colleague at school sitting with his head on his crossed arms, the book laid aside, utterly devastated by the first 75 pages. McEwan’s gift for expressing the immediate moment framed by an inchoate sense of its place in time remains unique though his works have gradually become more uneven as his fame and the world at large clearly reshapes both his writing and his thinking. At the bottom of this brief letter, I have ranked his novels though it, like most such lists, is ultimately an unreliable source, even for me.

His most recent book deserves its own letter. It has been a while since he wrote a book that really arrested me. The last book that “worked” for me was The Children Act (2014) and before that Sweet Tooth (2012). Neither however had the heft, the “stick with you” depth of his earlier books, the last of that quality being Saturday (2005). It has been a long wait and that certainly influences my embrace of his latest, What We Can Know.

Strangely, I am more comfortable approaching this book from its faults. A few of these plague most of his recent fiction and remain an obstacle for many readers. One that gets much attention, is his almost too transparent cleverness. I do not mean the trick ending of Atonement or the use of “Dover Beach” in Saturday; rather, his brazen exercise of his erudition. This is particularly true since he launched into the sciences as material for his previously all too humanist novels. Much of it felt like showing off and the first 50 to 75 pages of his latest novel flirts with this alienating flaw. Though it never really leaves the novel, after your initial difficult descent, the characters, the plot twists and the themes in What We Can Know begin to shape a powerful novel. In a related area, I have struggled with his preachy embrace of the topical – all part of his science adventures. Climate change is, after a long and deafening silence, finally the topic of choice in fiction and this is McEwan’s contribution. Though I wish he had resisted his pat treatments of America on one end and Nigeria on the other, his handling of climate change is one of the strengths of the book. I cannot get it out of my head. Finally, the tricks … One reads McEwan waiting all the while for a shoe to fall. Sometimes it is a slipper (Sweet Tooth) and others it is a ski boot (Atonement). With very few exceptions (see his earliest short works), it is a signature of his writing that some think detracts from its many literary merits. Beyond plot twists and shifting points of view, there is only one trick in What We Can Know that matters, and it is a BIG one. It divides the book literally and figuratively. It works and then kind of doesn’t as I wanted another act to bring things into a greater whole.

So far, I can be excused of “damning with faint praise”. I am NOT dismissing this novel in the least. This is an ambitious, maybe even important book. It should be read, and it will be remembered. It may be the first time that he has successfully merged his literary gifts with his need to be topical and relevant. Great books are often deeply flawed. While not comparing this novel to any of the following, Moby Dick is peppered with chapters easily skipped, War and Peace ends with a thud and all of Dickens can be over wrought. But like Richard Power’s recent tour de force, The Overstory, McEwan’s latest novel rises above its flaws because it leaves a mark on the reader, a mark that will stick. Now for the list …

1. ATONEMENT … one of the great pure reads of my life. It has survived a very good film adaptation and the envy of his peers.

2. CHILD IN TIME … again, not to be read by a young parent; however, the first half might be as good as anything he has written.

3. ENDURING LOVE … strangely, a very pure McEwan novel where technique triumphs over plot.

4. ON CHESIL BEACH … teaching this intimidatingly intimate novel to high school seniors made me appreciate how finely tuned a story it is.

5. SATURDAY ... something had to follow the sensation created by ATONMENT and he gets high marks with this more claustrophobic novel.

6. THE CHILDREN ACT … a tough clear-eyed critique of the law framed by the pains of a struggling marriage – not an easy thing to pull off.

7. SWEET TOOTH … in many respects his “sweetest” novel … fun to read … an “entertainment” of sorts compared to much of his work.

8. AMSTERDAM … a short tart novel that became a platform for a long overdue Booker, though among his weakest and least memorable.

There are his short early novels. They include The Cement Garden, The Comfort of Strangers and Black Dogs. They are the product of the darker side of McEwan’s literary mind. They are tight and not ‘tricky’ … and in a couple cases, very disturbing.