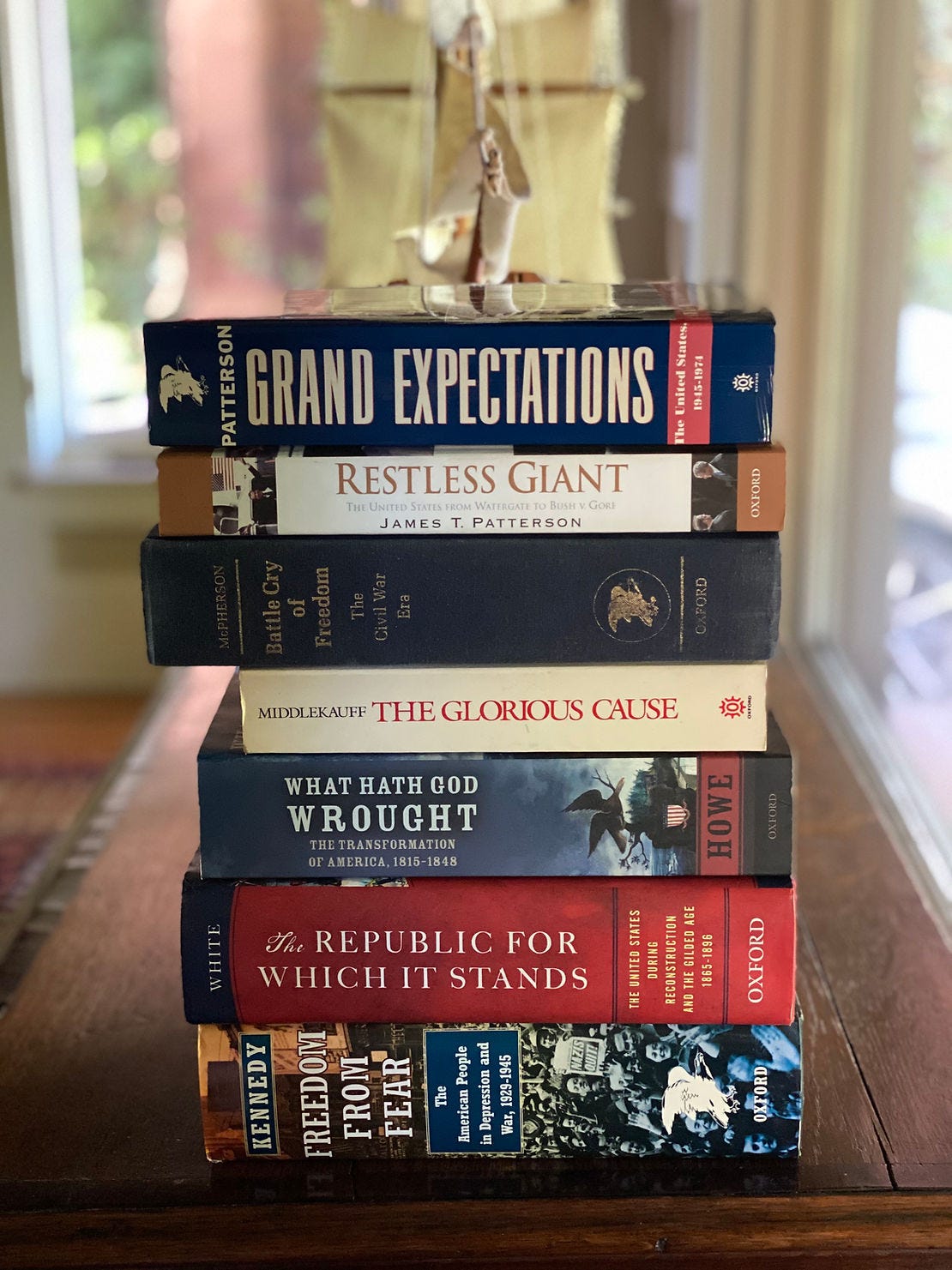

The Compellingly Different Volumes of the Oxford History of the United States

Over the years I have heard from many adults that they wish they could take an American History class and this time listen and remember. They also wonder if there is a good single volume history out there that is NOT a textbook. I never hear of anyone actually signing up for a class and as for the latter, there is one book out there that everyone should read – Jill Lepore’s These Truths. The “truth” is that outside of Lepore’s masterpiece, most books that tell our story are a single historian’s multi-volume attempt or out of date or too polemical or all of the above. A great way, however, to dip into this vast subject is to read parts of our history – maybe one part a year. The Oxford History of the United States is a good place to start. The following is an overview of the ambitious 60 year old project that has yet to be finished with two books on early 20th century America in the works.

The Oxford History of the United States is a multivolume publishing effort begun in the 1960s. There have been false starts along the way, different editors and, I am sure, plenty of controversy. The goal was to divide American History into 12 segments covering traditional periods ranging from Colonial America to the Civil War to the Great Depression. An historian noted for his (not a her yet!) coverage of that period would then write an engaging, very scholarly and often very long narrative about that period. The historian could emphasize whatever he wants, preferring a political, social or an economic perspective. So far, eight periods have been covered with two more on the way. There is a separate volume that specifically focuses on American foreign policy. The editor rejected some books because they had too narrow a focus. I can only imagine the politically fraught issues that accompanied each edition, particularly as of late. It is an uneven and at times laborious collection. Some are simply brilliant products of writing, synthesis and thematic construction. Others are much less so. The following is my overview of the eight – all of which I have read though some much more enthusiastically and carefully than others.

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era

by James McPherson (862 pages, 1988)

The book begins with the Mexican War and the terrible sectional battles unleashed by the western lands. It ends with the end of the Civil War. It remains the great narrative of the war, of its origins, and of all the principle players and passions that came with it. It is great political and social history while being an eminently readable version of the war itself – particularly for those not immersed in military history. It won every award and remains impregnable to this day. It will feel to a current reader chillingly relevant as we go farther and farther down the rabbit hole of extremist thinking and as we confront the issues left unresolved (or even exasperated) by the Civil War. When it comes to this vast, terrible moment in our national story, it is to narrative published history what the Ken Burns documentary is to film.

Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic 1787-1815

by Gordon Wood (732 pages, 2009)

I read this book at the start of 2020. My marginalia is all over its great length. It left me breathless with its relevance to our day. The political dysfunction, the shameless press, the lies and false news – it is all there, splattering our enshrined founding fathers and the nascent political world they had begun. Reading this book is very reassuring in unexpected ways. You realize that the founding fathers would NOT be surprised by today’s politics and our culture wars. This does not mean they were not deeply disturbed by how quickly and rabidly the country dissolved into a world of rancor and self-interest. They, practically to a man, left this world convinced that the American “experiment” was either already a failure or was certainly going to prove to be. This story is a brilliant one both intellectually and artistically. Gordon Wood is perhaps the finest writer among the handful of world-class historians from his generation. His sentences are as graceful and elegant as his arguments. This book may lead you to his other works on the Revolutionary period – all undeniable classics that changed the arc of historical thought.

Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression & War 1929-1945

by David Kennedy (860 pages, 1999)

This book has since been divided into two volumes. Not sure why given the length of most of these histories. It might have something to do with the very popular and slightly corporate Kennedy being the editor in charge of the series until just recently. This is a snarky start and I apologize. I may simply envy the skill and apparent effortlessness he brings to this massive story – the story of the rise of the American Century. The subject alone is breathtaking in its scale and Kennedy captures all of it in this great book. It is filled with acute scholarship, terrific anecdotes and profiles and an evenhandedness that seems even more valuable in our unleashed times. While all the usual suspects (FDR in particular) tower through this narrative, Kennedy’s treatment of the common man’s experience during these years is particularly effective. Terrible things and terrible people brought on those events. Terrible things went unaddressed and terrible Americans behaved terribly. Above all of this, however, is the deeply stirring story of a flawed sleeping giant awakening to face adversity and evil. It will stand in the distant future as one of human history’s great narratives. That was NOT a piece of American Exceptionalism; rather, it was a reality movingly and flawlessly captured by David Kennedy.

Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974

by James Patterson (790 pages, 1996)

Look at those dates … the dates of Pax Americana … the dates when America shaped the postwar world in every way. The dates where a high school degree was all that was needed to get all of the American Dream that mattered – if you were white (preferably male) and straight. That means barely over a third of America were its direct beneficiaries – they and their boomer children. Regardless, the darkness was gradually lifted around many of our original sins while the “other” people everywhere began to be heard and, all the while, the music was simply off the charts. We walked on the moon, watched Sputnik rotate above us in the darkness, wept at JFK’s assassination and slowly woke to the terrible mistake of Vietnam. We took birth control pills, joined cults, moved into suburbs, divorced, popped acid and rode Freedom buses. It was a twenty-year period that will elude historians for a long time to come. It is being fought over each day today. It is relentlessly fecund and fraught. Patterson’s history is restrained, thorough and modest. He lets the events, most of them that we witnessed in one semi conscious state or another, tell the story – and what a story.

… here the drop-off begins …

The Republic for which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age

by Richard White (870 pages, 2017)

This is the most recent volume and it bears the marks of a complicated, even tortured story beaten into politically acceptable shape at the expense of both the narrative and an intellectual depth and restraint that would allow this expansive book to survive the test of time. It is at the top of the minor league list of Oxford histories because of the historian who wrote it and the subjects it had to cover. Richard White wrote a book about the 18th century worlds of white settlers and traders mingling with the still relatively intact native worlds entitled, The Middle Ground. His title became part of our language since the book was a shocking piece of original scholarship that established a new paradigm of sorts. His writing is excellent and in this recent book there is a lot of it. I was, however, deeply disappointed that he did not rise to the level of thematic mastery and insight that this period of history not only requires but suffers from the lack thereof. Reconstruction is so painful and complicated – like any “failure” in American history. While its failure is both accurate and the accepted narrative, even that is laced with qualifications. As for the Gilded Age, we are living its redux version today. No era of American history requires more insight, gravitas and contextual nuance than this period. It was our volcanic moment, filled with terror and destruction but the source of an irresistible force – an emerging empire. White gets his coattails caught up in too many social issues and too often writes through the lens of self-righteous hindsight. It was a good read with some unforgettable anecdotes and profiles of individuals off the beaten track; however, I fear that is where the book is destined to rest.

What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America 1815-1848

by Daniel Walker Howe (858 pages, 2007)

This is a long book that feels even longer. I am not sure what happened to this book. Maybe I tried to read it at the wrong time. I ended up skimming parts of it as I rushed through to the end. I have a real prejudice against Jackson and the Democrats of that era. It is hard material filled with the ignorance and violence of a partially democratized nation utterly unable to resist grabbing everything within her continental reach. There is so much that is relevant. The rise of America’s Protestantism into the national mainstream, Jackson’s populism, manifestly irresistible territorial expansion and the art of living in denial of certain tragedy. Howe writes in a way that suggests it was too much for him. I should be more sympathetic. This period, particularly after 1824, begs for a more visceral almost Shakespearean treatment. Bad things are happening, something is rotten, an empire is taking shape and all of this within a torrent of lies and ignorance. Perfect stuff for another writer and maybe another time …

Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v Gore

by James Patterson (420 pages, 2005)

I loved it until I didn’t. It is all too close to the bone. History really requires a lot of time in order to become something not vibrating with the resentments and prejudices of the lived experience. We are barely getting a grip on the Fifties. The Sixties remains a claymore mine of invisible trip wires. How can we look at Reagan with any impartiality? A hero to those who benefitted from the wealth creation he unleashed and a villain to those who suspect that our vast inequality may eventually be our undoing. What DID Clinton do, by the way, and after Trump even the then terribleness of George W looks comparatively benign. The Supreme Court decision in the title may eventually overshadow even 9/11 as THE moment when things changed for good. Who knows … too bad. Patterson is a good writer but does seem to be mailing this in a bit. He knows he is working with clay not stone. It is short – as it should be. Read those long ones at the top of the list. They are worth it.

The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution 1763-1789

by Robert Middlekauf (662 pages, 1982)

The first and the weakest … the Oxford folks had to start somewhere. This is a story asking to be retold – no SCREAMING to be retold. The writing is uninspiring and too much has been revealed since its publication. It is out of date but we must thank Middlekauf for being the guinea pig in a great historical publishing adventure.

Postscript: if you are a student of mine, you will see the obvious flaw of all I have just written. The four volumes I loved covered the periods of American history that made teaching sublime. Each of these periods were potential La Brea tar pits where my progress stalls amidst detail, stories and enthusiasm imperiling my ability to get to 1980 by the end of May. On the other end, there are the gravity free zones of Jackson, Reconstruction and recent history where I could feel the attention spans getting shorter and shorter – including mine. The exception to this construct is my fascination with Colonial America, which, as I said earlier, needs a retelling. So … please accept this acknowledgement and then give one of these books a shot.

I appreciate these reviews, however late I am to finding them. I have decided to integrate these in with my reading of presidential biographies, and plan to read Glorious Cause and Empire of Liberty once I finish a biography on James Madison. I'm hoping variois biographies and these can give me some frame of reference to the maddeningly distraught times we find ourselves in and some amount of hope and confidence for a way out with something better on the horizon. Maybe by the time I've worked my way through these books and President Wilson, Bruce Schulman's entry covering the Progressive area and Roaring twenties will be released!