Why Read EMPIRE: How Britain Made the Modern World

Another book on the British Empire ... now?

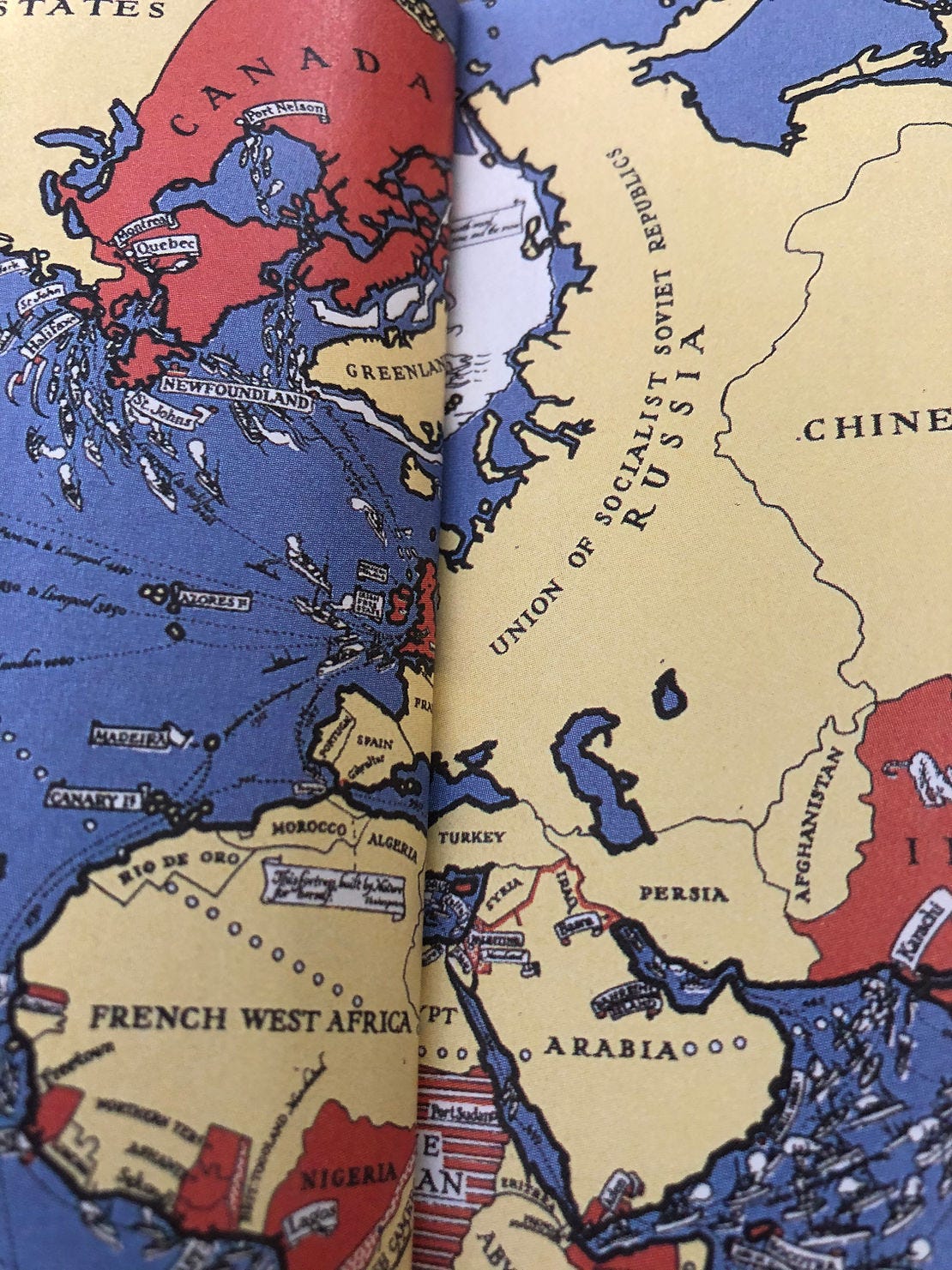

Niall Ferguson wrote this history of the British Empire in 2003. Much has happened to Niall, the British and history itself over those 17 years. Niall has become a darling of conservative scholars and a flamboyant example of a good historian, decent writer achieving the dubious distinction of a quasi celebrity. As expected, with each additional rung in the celebrity ladder, the freshness and vitality of his scholarship is increasingly muted. The good news is that this book reflects a younger, hungrier Niall who had not yet abandoned the rigorous standards of good historical scholarship for the klieg lights of money and fame. There are many things wrong with his book, regardless of his sincerity. It is especially weak as it turns toward the 20th century. The decline of the British Empire remains too current and as such his post WWI work feels political and reductionist. The first two thirds of the book, from the 16th to the 20th century is a terrific romp through an empire begun on the shoulders of pirates and 300 years later marked by maps advertising 1/6th of the globe as subjects in one form or another of the British. In the middle is a clumsy and almost laughably parochial treatment of the American Revolution. Despite this blizzard of issues, it is a terrific read – one beautifully illustrated and footnoted.

As for the British, it is hard to read if there are parts of the imperial project that remain near and dear to your heart. The Britain in his book reminds you of her better half – a people with a true spirit of adventure, real wit and a long legacy of technological and financial innovation. Niall does a tolerable job of reminding you that along with these virtues came a bag of horrors ranging from introducing to the world all forms of modern addiction, facilitating the slave trade and native exploitation in order to grow, ship and sell these addictive wonders as well as a capacity for violence intimately attached to xenophobia and sexual repression. Much of it is familiar but some of it is framed in ways that will startle you. For good or bad, however, the Britain he describes no longer exists as it shrinks into its xenophobic id. Maybe they deserve it. Maybe Brexit is the last ironic expression of imperial delusion. Regardless, there is a sense of loss reading this book in 2020 – a year of steadily increasing unease, dread and disorder. The “center” no longer seems to be holding – define “center” as you will. Warts and all, there is no denying that the British Empire served as a “center”, a counterweight to the entropic nature of human beings and history itself.

Finally, this is old-fashioned history. Niall gets stuck on many things – mostly his parochial Tory outlook. However, he does tell a straightforward story that is not mired in self-referential misfortune or grievance. The bones of history are here to be picked over. He builds a worthy skeleton of a grand story. Too much history today lacks cohesion and discipline and is too often an excuse to rant and judge. A little of the latter permeates this compact narrative (particularly the more current it gets); however, in the end a structure has been built that has the integrity of history well researched and reasonably curated.

What I propose to do next is outline my “walks with Jeannie”. While taking hikes in Idaho during our Covid summer of 2020, Jeannie would ask me to tell her something about the British Empire. This happened so frequently that I began to annotate the blank back pages with summaries of anticipated “walks with Jeannie”. The following are expansions on those annotations and condensed versions of the walks.

PIRACY:

The British Empire began as a pirating enterprise. Sir Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh and many more made and lost fortunes chasing down the treasure ships of the Spanish Main. One seizure brought back to the Crown enough treasure to retire all royal debts. This was serious business on both sides with the treasure ships fueling the sprawling, fiscally insatiable Spanish Empire and the pirates fueling a relatively tiny but aggressive island nation in its efforts to remain independent. This will not be the first time that England (or “Britain”, after its union in 1700 with Scotland) accesses private resources to fund and staff imperial expansion. The American colonies were initially settled by commercial ventures. The West Indies and the sugar industry that reshaped British fortunes and lifestyles were all private enterprises including the slave ships that trafficked the Middle Passage. India would be conquered and governed by the publicly traded British East India Company for over 100 years utilizing a private army larger than the Queen’s. Similar ventures were at the tip of the colonial spear in Australia and Africa. While the government would contribute the massive Royal Navy and a relatively small professional army as a guarantor of secure trading routes and cooperative native populations, the Empire’s modus operandi was through privately funded commercial ventures structured by the increasingly sophisticated financial gurus operating out of the City of London. Its commercial genius was the secret sauce to the ability of this small island on the periphery of Europe to give birth to the largest empire in world history.

NOTE: the Dutch Republic succeeded along similar lines. In fact, the English copied the Dutch’s use of a stock exchange and a central bank to fund

its overseas investments.

EMIGRATION:

Why did the British avoid throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the social upheavals and revolutions experienced by her continental rivals? This is one of the great questions in European history and Niall addresses it directly. The fuel for revolution was there. The “nabobs” from India and the West Indies were accelerating the restructuring of British society into an increasingly unequal, commercially corrupt world with massive rural displacement and urban homelessness. Despite the occasional riot and some political volatility, Britain remained relatively stable. Niall attributes this to emigration. She shipped her volatile elements to Ireland, America, Australia, Canada, South Africa and most anywhere else within the empire’s 13 million square miles (25% of the world’s land mass). The British Empire was settled by English indentured servants (America), the Irish (Australia & America), convicts (Australia), politically disruptive second sons (America & Ireland), Scots (India & Canada), the Scotch Irish (America), religious dissidents (America & Canada), zealous missionaries (India & Africa) and the young and restless (everywhere). The rise of The American Empire occurred along similar lines. With the huge exception of the Civil War, America’s expansion and the increasingly unequal wealth creation that went with it resisted domestic unrest for similar reasons. The West (which begins with the Appalachian Mountains) absorbed her most volatile elements for the first 300 years and, even after the country was fully explored and settled in 1900, she would backfill for another 60 years with African Americans migrating north, displaced farmers going West and most everybody else heading for California. Our continent was our great social sponge, acquired and settled with relative ease (REMEMBER: over 80% of the native population had been killed by disease by 1800). Much of what we are experiencing today is an angry and divided America where the answer can no longer be some version of “Go West Young Man”.

MERCENARIES:

The British Empire was built on the back of professional armies of various guises. There were the “corporate” armies of the British East India Company, staffed by British officers and Indian soldiers. After London took over India and effectively dismantled the British East India Company after the Mutiny in 1857, this army was reshaped into an imperial professional army that would be ruthlessly used in over 70 engagements throughout the empire. The tradition of a professional army bled into both World Wars as Britain never embraced conscription (e.g. a draft) at the level of her foes and allies. While this made for a remarkably effective army given its relatively small size, it also left the British people immune to the many wars her empire prosecuted in its almost 300 year history. Even in the 18th century, hired mercenaries did much of the dirty work. The wars with Napoleon were fought by a combination of the Royal Navy and Continental armies subsidized by the British. The war in Iraq has exposed the Achilles Heal of a highly trained professional army as our soldiers were sent into action over and over again but few Americans had any sense of the sacrifice involved. Mandatory military service or a draft brings such things into relief. A senator is less likely to vote for war if his son or daughter is going to be drafted. The British public put up with horrors of WWI in part because it was never brought home to it the way it was for the Germans as they slowly starved to death under the blockade. As revealed in the recent remarkable documentary “They Will Never Grow Old”, returning British soldiers from the Great War were too often told by the people at home to basically “get over it”. In France, on the other hand, the war began to belatedly infiltrate the French public and in the spring of 1917 the army began to mutiny. The horror of the war and the mind-boggling loss of life suffered by the Russian army was the straw that broke the back of the Russian monarchy. Though the recognition of such terrible realities is often violent with terrible consequences, wars that are “brought home” may be wars that are not fought to begin with. Our professional army today may be the finest in the world; however, like the British imperial armies, it is a weapon too easily brandished. It is a service rendered by too few. It is, ultimately, undemocratic. Though the President is the Commander in Chief, the army is not HIS army; it is the people’s. A conscripted army requires the possibility of mandatory service for every American youth and a much greater likelihood of “declared” wars. Talk about checks and balances …

ADDICTION:

Niall introduces a very provocative way of thinking about the British Empire. He attributes the commercial success of the empire to many things but one that gets particular attention is the rise of the British consumer – the world’s first consumer class on a mass scale. Though the American consumer of the 20th century world dwarf this 19th century version and will be the prototype for the world, the consumption culture began with the British Empire. It began with and expanded on the highly profitable human weakness known as addiction. Niall goes so far as to label the British Empire as an empire of addiction. Though a bit reductionist, it makes sense. The massively popular sugar plantations of the West Indies generated a nation addicted to sweets. Soon British confections became a trademark of empire. Britain remains, to this day, the sentimental “sweet shop” of the west. “The Great British Baking Show” is a direct by-product of those sugar plantations of the 18th and 19th centuries. Tea was the kissing cousin of sugar as one promoted the other. The working class male consumed vast amounts of sugar with his tea, disguising shocking levels of malnourishment in the industrial working class. Soon, the typical working class male would be over 4 inches shorter than his well-fed upper class counterpart. One reason the British army held together during WWI was the fact that so many working class youths were willing to trade in the trenches for the promise of being decently fed. This legacy of malnourishment is directly tied to the marketing of sugar and tea and … tobacco. “Brown gold” from the Americas would become another great British export and omnipresent feature of British life. All the great tobacco companies were initially British. While the fear of this deadly addictive product arose early on in its marketing life, the profit behind such a powerfully addictive product proved irresistible – as America would learn soon thereafter. Though the list of addictive products created and marketed by the empire is long, it cannot be completed without referencing the most odious example. The British desperately needed a product the Chinese wanted as much as the British public wanted Chinese tea and silk and other such niceties. The imbalance was draining the imperial silver reserves and bankrupting merchants and their City backers. The answer would be the forced entry of opium into the Chinese market; done so at the tip of the sword and facilitated by rapaciousness from both parties. The empire of addiction had now stepped into the most fatal and unapologetically mendacious of worlds. The whole question of addiction, however, can too easily be attributed to the Anglo American enterprise of the past 400 years. However guilty and remorseless both empires have been in creating a world of addicted subjects (see smartphone & Instagram), it is likely the fault lies with human nature and capitalism more than anywhere else. Maybe that is what, in the end, climate change is all about. It is the great rehab that awaits the human race.

There is much more in this book. The insights it sparks has less to do with the historical genius of Niall Ferguson and much more to do with the poignantly profound space left open by the retreat of the Anglo American world. Reading this book reveals how far reaching, brilliant and troubling at least the first half of that world was.

Finally, limiting myself to a single sentence, the following are a few more insights I took from reading this colorful, provocative, flawed but (in its own way) timely book.

India was at the very heart of the empire and no substantive decision was ever made without India being involved somehow.

Ireland’s gradual emancipation was doomed due to fears of what such a precedent might trigger in the rest of the empire, India in particular.

The Indians were more than complicit in their embrace of British colonialism.

Repressed sexuality, particularly homosexuality, played an extraordinarily powerful role in the aggressive adventurism and terrible violence that marked much of the empire’s growth, particularly after the ascendance of Queen Victoria.

Evangelical Christianity poisoned the British Empire every bit as much as it has poisoned the American Century.

The British (and later the American) Empire might have ben the best of a bad set of choices

The carving up of Africa in 1884 at the Berlin Conference (initiated by Otto von Bismarck) led to a continent of 10,000 tribes being reorganized by the European nations into 40 artificial nation states in only 30 years (think about that …).

The partition of India in 1947 was a disaster that had no historical precedent in the region’s long history.

The initiation and/or participation in the dividing up of Africa (1884), the Middle East (1919) and the Indian subcontinent (1947) were the basis for much of our present international instability.

Can we address climate change without the order and stability that comes with empire?