Why Read - Graham Swift

Graham Swift was born in 1949. He is part of a generation of English writers that I have followed for much of my adult life. They include but are not limited to Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan, Jane Gardam and Hilary Mantel. Each writes in their own imitable style but they share certain things in common. Their stories are often a mix of the big and small picture. Their novels range from contemporary meditations on the modern world, to historical fiction, to elegiac but honest treatments of post imperial Britain to the standard fare of people in small towns making do. Swift came to me very recently. He is likely the most “British” of the writers. He fills shelves in bookshops in London but makes barely a dent in my local store in Pasadena. I shipped home a couple more of his works hoping to get through much of his body of work by year-end. There are no tricks to his style (e.g. McEwan) and no consistent oeuvre from which he operates (e.g. Mantel and historical fiction). The three books I have read are markedly different narratives. They share, however, a thematic purpose that I will dwell on in this submission.

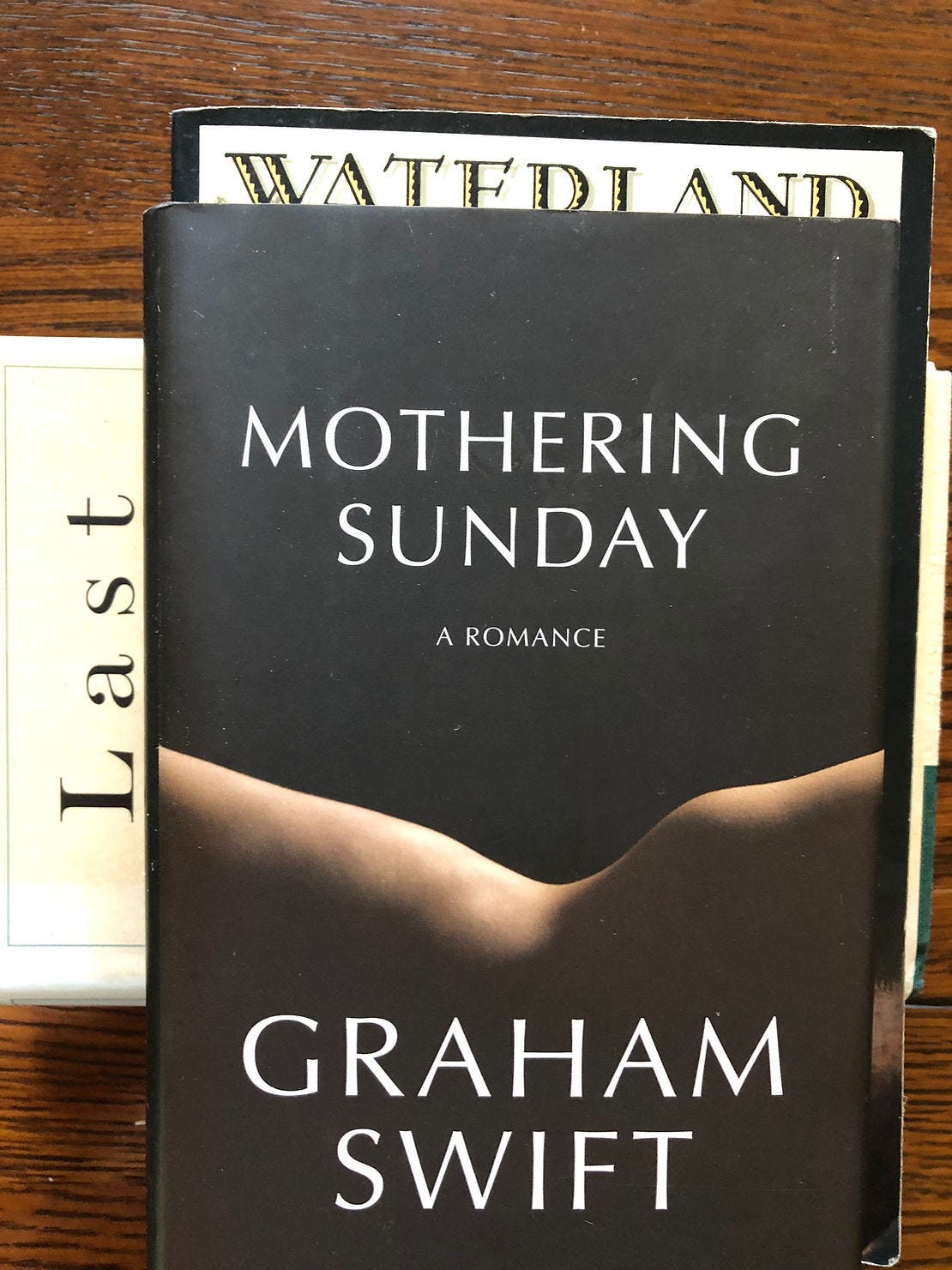

Mothering Sunday was published in 2016 and is his most recent. It was my first Swift novel. It is very short. I read it in two days and then began to hand it out to my friends. It has a “day in the life” structure to it and involves a “mothering” Sunday in the countryside of England amidst the unfolding horror of World War I. It embraces change, class, love and loss in 177 beautiful, lyrical pages. Time seems to be Swift’s subject in each of the books I have read, and the role of history and writing are often the mediums through which he wrestles with our “mortal coil”.

“It was about being true to the very stuff of life, it was about trying to capture, though you never could, the very feeling of being alive. It was about finding a language. And it was about being true to the fact, the one thing only followed from the other, that many things in life – oh so many more than we think – can never be explained at all.”

This excerpt is at the end of the novel (not a spoiler) and the “it” is writing. Writing is a metaphor for life in this novel. His world is not one of happy endings or comforting reconciliations. Rather, it reflects an honest attempt to evoke the reality that our temporal lives are all we have and they are filled with the facts of being alive – beautiful, painful, mundane facts.

I read the next book in Maine after finding it in a used bookstore. Waterland is longer, less an elegiac poem and more a dense story of water, love and change. It has a slight Watership Down feel to it as he writes about a world irrevocably lost but still alive in the our collective romantic imagination. History is his meta subject – again his way of addressing the changes and the often heart breaking circumstances of the novel.

The following excerpt reveals nothing in the narrative but possibly everything about why Swift wrote this novel 27 years ago. The fact that he addresses the word “why” was irresistible as I often began my history classes with that word as the reason I was standing at the head of the class about to embark on yet another 300 years of American History. Also, to frame it in a way I hope Swift respects, I would too often find the word too prosecutorial to manage in my own life. Maybe the word’s role in history is where I could make peace with it. Given this novel’s place in a lost time and its acutely and often painful treatment of timeless human emotions and mistakes, I like to think this is what Swift tried to capture in this remarkable novel.

“And what does this question Why imply? It implies … dissatisfaction, disquiet, a sense that all is not well. In a state of perfect contentment there would be no need or room for this irritant little world. History only begins at the point where things go wrong; history is born only with trouble, with perplexity, with regret. So that hard on the heels of the word Why comes the sly and wistful word If. If it had not been … If only … If only we could have it back.”

The semaphore of Why and If is the perfect spot to discuss the third novel, Last Orders. Written in 1996, it earned him the Booker that he is so often and so deservedly nominated for. It was adapted into a 2001 film starring several of the great men of British cinema: Michael Caine, Bob Hoskins, David Hemmings, Ray Winstone and that great manager of such men, Helen Mirren. While I urge you to read the book first, the movie is a faithful treatment that accomplished what adaptations so rarely do. It fills out a novel that is sparse in its prose but expansive in its characters. Last Orders is unlike the previous two. It reads more like a stage drama and does not have the lyrical asides of the two other books. The effect, however, is powerful. You begin to read between the lines and to connect the dots, gradually arriving in the same profoundly moving terrain of the other two books.

I hope I get to his other books. Meanwhile, I suggest reading him in the order discussed. If nothing else, read Mothering Sunday …

Mothering Sunday

Graham Swift

177 pages 2016

Waterland

Graham Swift

310 pages 1983

Last Orders

Graham Swift

295 pages 1996