Why Read MIDDLEMARCH

George Eliot's 800 page masterpiece felt just right as 2024 begins to unfold ...

The following is my reaction to rereading Middlemarch by George Eliot. This response is not meant to provoke guilt that you might not want to read an 800-page novel with many pages lacking even a paragraph break. The sentences are long and complex – the stuff of Henry James. There are a LOT of double negatives, some local politics that require a visit to Google and a whole nest of characters related directly and indirectly. One does not sit down and read this book for 15 minutes or before bed. That said … this reading (and the “listening” that came with it), will remain with me forever and, as such, I thought I might try to put into words a concise portrait of my response to Eliot’s masterpiece.

A lot of real adults like this novel, not just those who rank the greatest novels … but a 90-year-old ex-nun, ex-English teacher who has actually taught it and takes no prisoners and provided me with the final push to reread it. Apparently, it was at the top of Freud’s list and it was Virginia Woolf who famously pronounced it “one of the few English novels written for adults”.

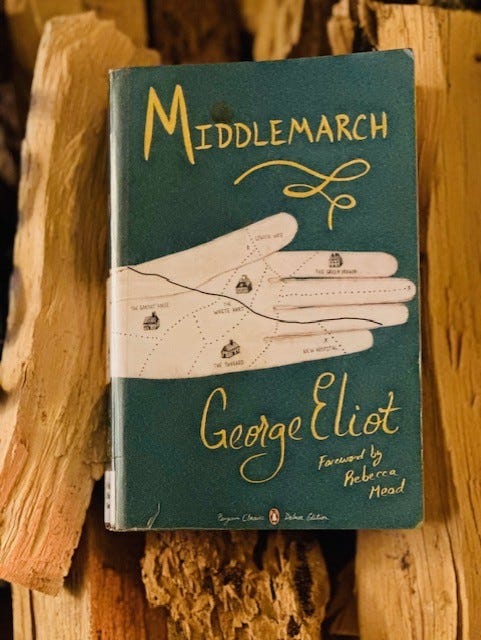

I never taught it. I read it once 18 years ago, in small bites over many months and barely glimpsed what all the fuss was about. When writing my “tending the garden” newsletter in January, I began to conflate this vast, deeply respected novel with an equally vast garden in need of tending. A spark had already been ignited by a typically insightful James Wood review of a literary biography of George Eliot that added whole dimensions to both the writer and her crowning achievement, Middlemarch. Woods clearly considers this novel to be at the head of the long list of Victorian marriage plots. With all this in mind, leaving my beat-up Penguin edition on its shelf, I marched to the library and checked out a well read but very readable edition and began … 18 years older and with all that comes with that. It was all that I both expected (difficult) and hoped for (brilliant) until the unexpected happened. My friend the ex-nun struck. She suggested I check out the Audible version. Given her long experience with the novel, I did. I started listening to the Amazon only version read by an extraordinary Maureen O’Brien and the novel went to another level. O’Brien’s reading gave elasticity and nuance to Eliot’s long and layered sentences. I was soon reading the novel with her voice as my muse. I finished in print but likely listened to at least a third of it on Audible.

NOTE: my unidentified ex-nun was, in fact, inspired by the ‘other’ reader, Juliette Stephens. It seems there exists a healthy debate as to which of the two gifted readings is the best. A fun choice …

There are many insights that I must share. In fact, insight is this novel’s middle name. None of the following will spoil a plot that unfolds at a glacial pace.

1. Operating at a depth mirrored only by the great Russian writers and Henry James, the principal characters are revealed such that their actions are perfectly understood by the reader. James’ Isabel Archer and Tolstoy’s Levin are reproduced throughout the countryside of Middlemarch. Eliot goes to the heart of the matter with an omniscient narrator not tainted by satire or stereotypes but equipped with an x-ray vision of the many human hearts that frame her story. It is so thorough that one sees parts of oneself in all the characters thus laying the groundwork for a reading experience rooted in one of her central themes, our struggle with self-awareness.

2. Middlemarch is called a ‘study of provincial life’. It certainly is at many different levels; however, I am still trying to figure out what that apt description really means. My long sojourn through the environs of Middlemarch frequently produced echoes in understanding and feelings about my sunny, very American home in 21st century Pasadena. While on the surface this novel is NOT Dickens’ 19th century urban dystopia, one wonders if his London is simply a melodramatic version of what lies at the heart of both worlds.

3. The voice of Maureen O’Brien brought home the intensity and brilliant illuminating power of Eliot’s prose. Her writing has within in it an orthoscopic quality – it reveals without distorting disturbances. Going back and forth from her voice to the printed page was an exhilarating experience.

4. An FT columnist recently wrote about the joys of the LONG novel. Its length makes it that much more a part of your life. I carried a used hardback edition of War and Peace all through New York City for over three months when I first read it in my youth. The reading experience soon took on a physical quality, it became a part of the quotidian of my life. Books are often praised for their intimacy. The time and commitment required of a lo

ng book, however, can foster intimacy at a different, often less manipulated level. It has hitchhiked into your conscious and unconscious management of your life.

While I read parts of non-fiction books along the way, Middlemarch occupied my fiction universe for weeks. Experiencing a difficult separation from the 19th century, I have returned with gusto into contemporary fiction. In a year freighted with profound historical implications for both this country and the world, non-fiction has felt strangely remote. My garden is a fictional one at the moment. More on that in the next letter.

Thank you for reading …

Peter, your insights into literature provided by this privileged glimpse into your reading diary is essential reading for me. Thank you!