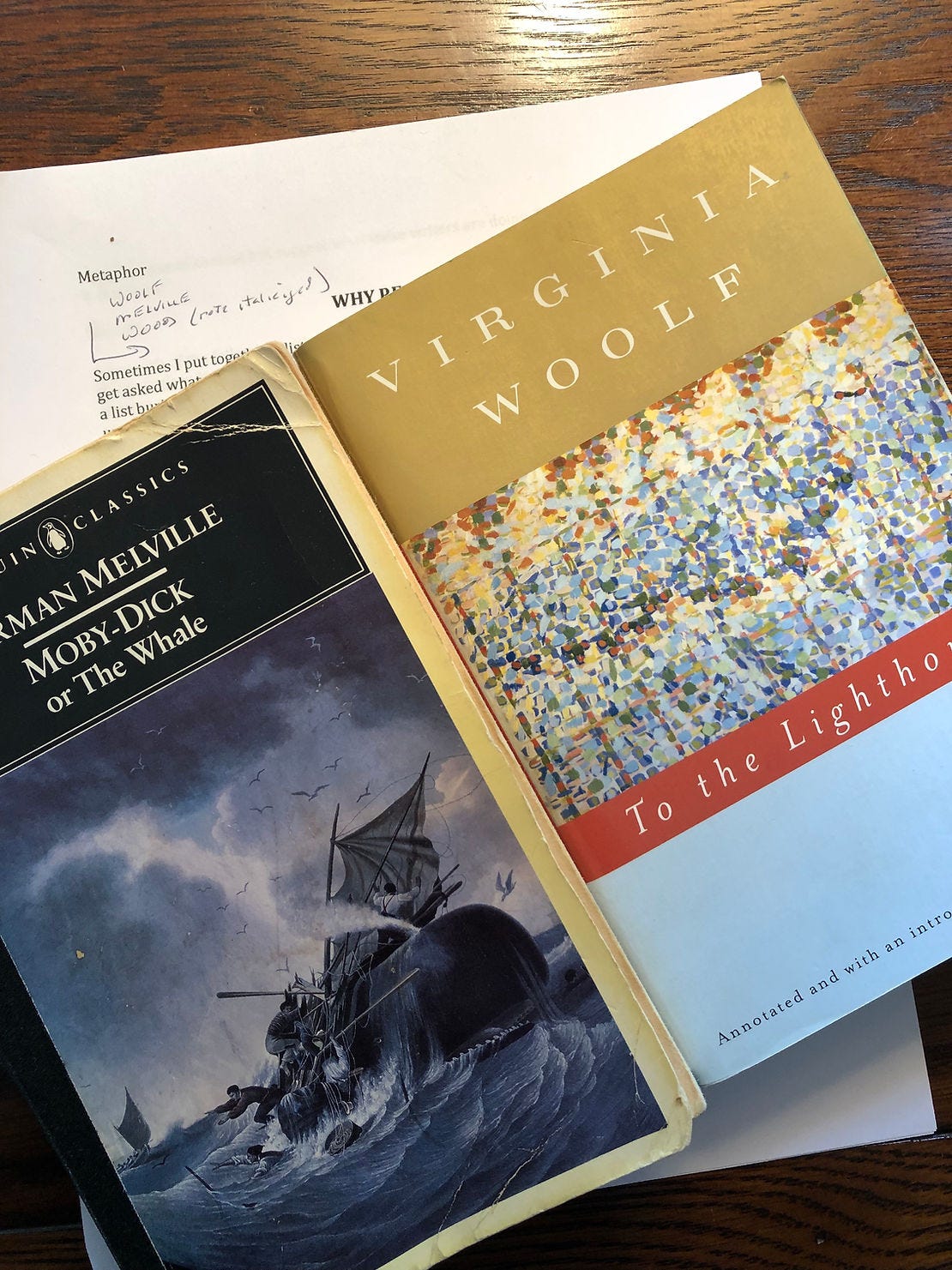

Why Read - Virginia Woolf & Herman Melville

Sometimes I put together a list of my “desert island” books. Every once in a while I get asked what are my favorite books. Certainly students asked me each year. I keep a list buried on my “Books” file in my i-Phone Notes app. I never or very rarely update it. For all the right reasons, it is as equally hard for a book to “get on” the list as it is to “get off” it. Two of the books that have sat atop the list for the past twenty years are To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf and Moby Dick by Herman Melville. I taught the former for three years to seniors – a real trick. As for Melville’s “evil” book, only one sophomore literature class in twenty years volunteered to read the whole thing. All the others read my heavily curated version as part of an annual winter’s argument between Emerson and Melville about … everything.

I believe in these two books. This is a belief that borders on the religious. I believe in them for what they try to do and this brief essay is not the place to unpack all of that. I continue to read Moby Dick out loud to my wife each time we go to Maine in the fall to escape the Pasadena heat. Whenever a friend or relative reads To The Lighthouse, I pause knowing that a long relationship may be mildly tested by their reaction. My son called me many years ago to tell me that he had picked up my marked-up edition from the bookshelf and found himself two hours later sitting on our street’s concrete bridge not even aware that he had walked there. It remains among the most personal of literary affirmations I have experienced.

When I talk with people about either of these books, they almost always ask me why are they so important. My answer too often sounds either a bit weary or a bit much. Not to put too melodramatic a spin on it, but it is a bit like asking why you love your children. Recently, however, I was given a collection of essays written by the justly famous New Yorker book critic, James Woods. My friend and mentor, John L’Heureux gave them to me shortly before he died. It is shaping into the timeless gift I suspect John hoped it would be. Always a James Wood fan, I now thank this toughest of critics for providing an answer of sorts to that question of why I am so wedded to these two books.

Both writers rely on the metaphor to convey the meaning and purpose of their works. A metaphor describes meaning through a representation that is not literal. It avoids the literal to suggest what cannot be fully illuminated literally. Basically, it is a flashlight in the immense, boundary free cave of metaphysics. This is where these two writers take you in each of these novels - very different caves, similar flashlights and the same darkness. This is the moment I hand it over to James Wood. The following are a selection of quotations from his essays on Woolf and Melville. They are taken out of context but suggest what these writers are doing. Treat them as … metaphors.

Melville

Read each of the following with this (to leap off the cliff of reductionism) in mind …, Moby Dick is Melville’s argument with God – about his (God’s) existence, his silence and his relationship with us. Ahab is the fictional embodiment of this raging argument within Melville – an argument that will destroy Ahab and drive Melville to the brink of madness.

“Soaked in theology, Melville was alert to the Puritan habit of seeing the world allegorically, that is, metaphorically. The world was a place of signs and wonders …” (All religions use symbols to “explain” faith – using a symbol to suggest what cannot be honestly accessed literally. The white whale is the symbol of literary symbols because, in no small part, of its religious connotations)

“So Melville slapped at God. He could not help playing the infidel … metaphysics could not stop like a day trip at some calm watering place. Dialectic was always an elastic solitude stretching into the desert.”(Think of religious faith as that “calm watering place” and doubts as the “elastic solitude”. Dialectic is often felt to be a pretentious word because – it is. It is a good word, however, to know. Think of it as an eternal conversation where the answer lies in the back & forth of the conversation.)

“It was Melville’s love of metaphor that drew him even further into ‘Infidel-ideas’. Metaphor bred metaphysics for Melville.” (Think of a metaphor as the opposite of an answer – the question as pi. The book felt “evil” to Melville because the metaphors of the white whale, the whaling ship, the ocean and most everything else in the book only pulled Melville farther and farther away from the calm and more certain waters of faith.)

“Of course, no one is actually forced by metaphor, except a madman.” (Ahab and his whale … Melville and his God … they both had no choice).

Woolf

While reading these, please keep in mind that Woolf’s great novels (To The Lighthouse, Mrs. Dalloway and The Waves – yes … in that order) were efforts to ‘unwrap consciousness’. She believed that “it was impossible for us not to think about something, even if the thought is merely the process of forgetting something” (JW). She felt that this dynamic; this series of colliding, chaotic waves within us was our interaction with Time. This is what she tries to capture in these difficult novels. Clearly she never thought you could “capture time in a bottle”.

“A painter … can actually mix paints, but a writer cannot do this. The closest a writer can come to this is the yoking of metaphor, whereby one thing is pushed against another, and flashing simultaneity is achieved.” (Looking away from a star in order to see one is one way to think of it.)

“Metaphor is the way to explode sequence.” (And thus simulate our very non-sequential minds. She believed that we seek traditional fiction in order to take comfort in its straight-line narrative precisely because our minds refuse to work that way. She wanted to capture the chaotic music of our thoughts.)

“This contradictory belief, that truth can be looked for but cannot be looked at, and that art is the greatest way of giving form to this contradiction, is what moves us so intensely.”

(I do not think we as a species would have created so much trouble for ourselves and the planet if truth was something you could look directly at. To be utterly concrete and political, try “looking” at the abortion argument. One reason it is so black & white for so many is that it isn’t.)

“Her work is full of the sense that art is an ‘incessant unmethodical pacing around’ meaning rather than toward it, and that this continuous circle is art’s straightest path. It is all art can do, and it is everything art can do. And finlike, the meaning moves on partially palpable, always hiding its larger invisibilities.”

(Mr. Ramsey, the philosopher father figure in To the Lighthouse, and Ahab insist on a straight line – no “partially palpable” circles for them. The “fin” is the tiny exposed part of the shark. The tip of the iceberg is the same analogy. Art suggests not only what might be underneath but, most importantly, that what matters, what is meaningful is underneath.)

The language of both writers threatens all readers. Each begs to be read out loud. It is comforting to read them out loud. Putting a voice to their circling efforts honors both the beauty of their words (so many words) and their mystical ambition to reveal all that lies under the surface of our lives.